|

King's Own Royal Regiment Museum Lancaster |

|

|

HOME Museum & Collections Sales Donations Events Contact Us REGIMENTAL HISTORY 17th Century 18th Century 19th Century 20th Century First World War Second World War Actions & Movements Battle Honours FAMILY HISTORY Resources Further Reading PHOTO GALLERY ENQUIRIES FURTHER READING LINKS

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum. |

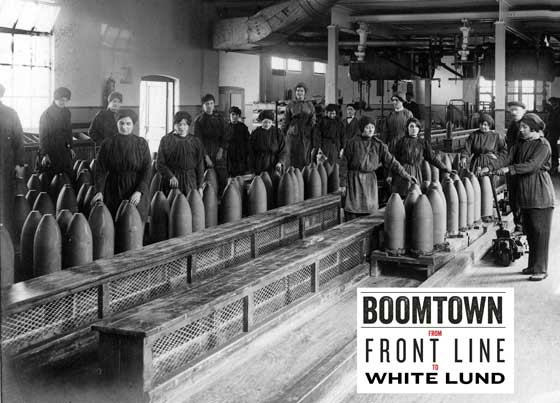

The Great War Centenary 1917 - Exhibition Boomtown - From Front Line to White Lund Who worked at NFF No. 13?

Munitions workers were recruited from all over. Direct approaches to

Lancaster Corporation, in April 1915, meant 80 employees were ‘released’

from council duties to work for Vickers.

Many women talked about changing at the factory but the photos of Market

Square and the Electric Buses, alongside the piece in the Visitor

newspaper’s Mustard & Cress column, in 1916, suggest that women wore

their uniforms with pride even outside of the works: Change Houses Change Houses were where workers changed from outside clothes into

uniforms. Change Houses had lockers where people left food etc. but

smoking materials, would have been left outside the main gates. Once you

had brought even a match onto the site you were guilty of breaking

Defence of the Realm Act regulations. Gardens & Canteens Alongside the main industrial works an area of the site was used to

grow kitchen garden produce. At times munitions workers swapped shell

filling for gardening. This may have been if they were showing early

signs of TNT poisoning to take them off the production lines.

We believe the produce was used in the works’ canteen that was much

praised for the high quality of its food and fair prices. Having a main

canteen like this meant there was no need to leave the site at meal

breaks. Some workers brought their own food to work and ate in their

Change Houses. On the night of the explosions we believe most of the

staff were in the canteen or in various Change Houses and this,

undoubtedly, saved many lives.

In Lancaster the Maternity and Child Welfare Sub-Committee met with Miss Leach, Welfare Supervisor for the Ministry of Munitions on 14th June 1917. She proposed such a crèche for the local munitions workers, limited to 20 children. Although the sub-committee agreed to discuss the matter with the Sanitary Committee it is not known if this was ever realised. Women often made their own, informal childcare arrangements with friends and neighbours

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum. Only a proportion of our collections are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of our collections which are held in store. |