Regimental History - First World War

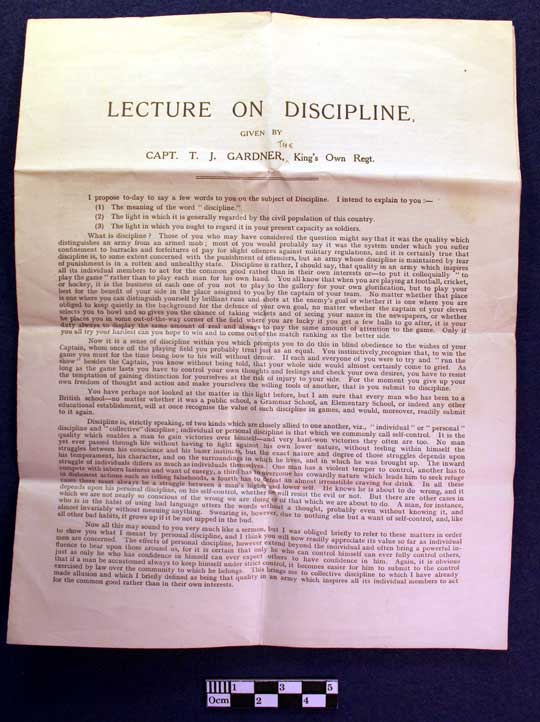

Lecture on Discipline,

given by

Captain Thomas James Gardner,

The King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment.

Thomas James Gardner was born on the 18th October 1882, he was

commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant on 12th July 1915 into the King’s Own

Royal Lancaster Regiment. He joined the 1st Battalion, in France and

Flanders, in October 1915 and was promoted Lieutenant on 14th September

1916.

Between 9th March 1916 and November 1919 he was seconded to the Machine

Gun Corps. He rejoined the 1st Battalion of the King’s Own in December

1919 whilst they were serving in Dublin. He retired with the rank of

Captain on 20th July 1921.

I propose today to say a few words to you on the subject of Discipline.

I intend to explain to you:-

1. The meaning of the word “discipline.”

2. The light in which it is generally regarded by the civil population

of this country.

3. The light in which you ought to regard it in your present capacity as

soldiers.

What is discipline? Those of you who may have considered the question

might say that it was the quality which distinguishes an army from an

armed mob; most of you would probably say it was the system under which

you suffer confinement to barracks and forfeitures of pay for slight

offences against military regulations, and it is certainly true that

discipline is, to some extent concerned with the punishment of

offenders, but an army whose discipline is maintained by fear of

punishment is in a rotten and unhealthy state. Discipline is rather, I

should say, that quality in an army which inspires all of its individual

members to act for the common good rather than in their own interests or

– to put it colloquially “to play the game” rather then to play each man

for his own hand. You all know that when you are playing at football,

cricket or hockey, it is the business of each one of you not to play to

the gallery for your own glorification, but to play you best for the

benefit of your side in the place assigned to you by the captain of your

team. No matter whether that place is one where you can distinguish

yourself by brilliant runs and shots at the enemy’s goal or whether it

is one where you are obliged to keep quietly in the background for the

defence of your own goal, no matter whether the captain of your eleven

selects you to bowl and so gives you the chance of taking wickets and of

seeing your name in the newspapers, or whether he places you in some out

of the way corner of the field where you are lucky if you get a few

balls to go after, it is your duty always to display the same amount of

zeal and always to pay the same amount of attention to the game. Only if

you all try your hardest can you hope to win and to come out of the

match ranking as the better side.

Now it is a sense of discipline within you which prompts you to do this

in blind obedience to the wishes of your Captain, whom once off the

playing field you probably treat just as an equal. You instinctively

recognize that, to win the game you must for the time being bow to his

will without demur. If each and everyone of you were to try and “run the

show” besides the Captain, you know without being told, that your whole

side would almost certainly come to grief. As long as the game lasts you

have to control your own thoughts and feelings and check your own

desires, you have to resist the temptation of gaining distinction for

yourselves at the risk of injury to your side. For the moment you give

up your own freedom of thought and action and make yourselves the

willing tools of another, that is you submit to discipline.

You have perhaps not looked at the matter in this light before, but I am

sure that every man who had been to a British school – no matter whether

it be a public school, a Grammar School, an Elementary School, or indeed

any other educational establishment, will at once recognise the value of

such discipline in games, and would, readily submit to it again.

Discipline is, strictly speaking, of two kinds which are closely allied

to one another, viz., “individual” or “personal” discipline and

“collective” discipline; individual or personal discipline is that which

we commonly call self-control. it is the quality which enables a man to

gain victories over himself – and very hard-won victories they often are

too. No man yet ever passed through life without having to fight against

his own lower nature, without feeling within himself the struggles

between his conscience and his baser instincts, but the exact nature and

degree of those struggles depends upon his temperament, his character,

and on the surroundings in which he lives, and in which he was brought

up. The inward struggle of individuals differs as much as individuals

themselves. One man has a violent temper to control, another has to

complete with inborn laziness and want of energy, a third has to

overcome his cowardly nature which leads him to seek refuge in dishonest

actions such as telling falsehoods, a fourth has to defeat an almost

irresistible craving for drink. In all these cases there must always be

a struggle between a man’s higher and lower self. He knows he is about

to do wrong, and it depends upon his personal discipline, on his

self-control, whether he will resist the evil or not. But there are

other cases in which we are not nearly so conscious of the wrong we are

doing or of that which we are about to do. A man, for instance, who is

in the habit of using bad language utters the words without a thought,

probably even without knowing it, and almost invariably without meaning

anything. Swearing is, however, due to nothing else but a want of

self-control, and, like all other bad habits, it grows up if it be not

nipped in the bud.

Now all of this may sound to you very much like a sermon, but I was

obliged briefly to refer to these matters in order to show you what I

meant by personal discipline, and I think you will now readily

appreciate its value so far as individual men are concerned. The effects

of personal discipline, however extend beyond the individual and often

bring a powerful influence to bear upon those around us, for it is

certain that only he who can control himself can ever fully control

others, just as only he who has confidence in himself can ever expect

others to have confidence in him. Again, it is obvious that if a man be

accustomed always to keep himself under strict control, it becomes

easier for him to submit to control exercised by law over the community

to which he belongs. This brings me to collective discipline to which I

have already made allusion and which I briefly defined as being that

quality in an army which inspires all its individual members to act for

the common good rather than in their own interests.

Now, does collective discipline, so defined, exist in armies alone, or

does it also exist in great civil communities and, if so, to what

extent? I have already mentioned discipline in games, the importance of

which is so fully realised by everyone who has ever been a British

schoolboy, and the existence of which proves that there is undoubtedly a

certain sense of collective discipline even in civilians, but I fear

that true collective discipline is a thing little understood, little

known and little practised by the civil population of this country. They

seem to look upon it as almost degrading for a full grown man to have to

submit to discipline, they consider it an interference with what they

call “the liberty of the subject.” and I firmly believe that the

prevalence of this view amongst the British public is to some extent

responsible for the difficulty we had in obtaining sufficient recruits

for our voluntary army. I have never been able quite to understand this

popular attitude, it seems to me strange that men who are so ready to

put up with discipline where other and more important matters are at

stake. It is because in the one case the necessity for discipline is so

obvious that they take it as a matter of course and have ceased to think

of it at all, whilst in the other their inability or unwillingness to

think far enough prevents their realizing the benefits which true

collective discipline would confer on the Nation and on the Empire? Or

is it – and this seems most likely – because in their every day work, in

their daily struggle for existence, where it is a case of each man for

himself, they have forgotten the discipline of their schoolboy days, and

have lost the power of subordinating personal interests to the interest

of the community?

Let us examine this last question a little more closely. The large

majority of young civilians leave school and school discipline at a

comparatively early age. They enter some factory, some office, or are

appointed to learn some trade, and then their struggle for existence

begins. Competition in considerable, living is expensive, and so the

youth of the people is often hard put to it from the first to make both

ends meet. He soon realises that it is a case of the survival of the

fittest, and that he must do all he can to keep his head above water; he

perhaps gets little or no help from home, and he is thrown almost

entirely upon his own resources. Small wonder then if he becomes

selfish, and if in all things his thoughts are of only gaining as much

as he can for himself and himself alone. Later on he marries, he has

others to provide for, and the struggle becomes severer still, but even

if he has been successful in his labours and has assured for himself a

position in which he can live in comparative comfort he has probably

been obliged to go through many years of hard unremitting and

necessarily selfish work. We cannot, therefore, be altogether surprised

if he has lost that power of striving for the welfare of the whole, that

sense of self-sacrifice, which animated him when playing for his side as

a schoolboy, and if his thoughts of his duty towards his country are few

and far between. The case of the well-to-do classes is similar but

though their sons are longer subject to school discipline and are imbued

with the excellent spirit engendered by our large public school and

universities, even they do not seem to appreciate to the full the value

of national discipline, of self-sacrifice for the common good and the

welfare of the Empire. In short, the conditions in which our great civil

population lives lead to selfishness amongst all classes, and to short

sightedness in almost all matters other than those with personal gain.

Sudden outbursts of even the most fanatical courage and patriotism can

rarely, if ever, avail against careful, scientific, and deliberate

preparation for war. A nation must makes its sacrifices, it must

practise self-denial, and submit to discipline for many years before it

can take up arms with any hope of success against a foe who has made the

science of war the object of his serious thought and study, and so also

do individual soldiers and officers require years to learn their duties

before they can possibly be of real value against a well trained enemy.

This the British people cannot understand, they cannot realise that the

profession of arms requires as much serious attention as any other. They

think that a soldier has little or nothing to learn besides the use of

his own rifle. Soldiering looks so simple, they consider that anyone

ought to be able to become an efficient soldier by spending an evening

or two in a drill hall every week, by firing a few dozen rounds at the

butts annually, and by attending a seven days camp once a year. But do

any of those who hold this view really believe that they could become

even moderately efficient subordinates in any other trade or profession

were they to treat it in an similarly light-hearted way? I think not.

Again, the civilian frequently cannot understand the need for drill and

so-called “barrack square movements” or their importance in relation to

discipline. He will tell you that rigid discipline, absolute submission

to the will of another, and the machine-like precision required by

“drill,” all tend to kill the spirit of enterprise in the soldier, to

destroy his individuality and to hamper him in the use of his own

intellect. People who talk in this way cannot but have a very poor

conception of what military training really means. They frequently

insinuate that “smartness” and perfection in drill are the principal

ends aimed at by officers, but I am convinced that no officer has ever

admitted these to be more than a mans to an end. It is no doubt true

that, especially during long periods of peace, “drill” has, at times,

been overdone particularly in countries where facilities for the higher

branches of military training were few, but this is no reason why we

should now fly to the opposite extreme and pay too little attention to

smartness and precision. We must never forget that men who are not

absolutely under control when within range of an officer’s voice and

vision on a level barrack square will be quite out of hand when spread

over undulating, overgrown country in the face of an enemy. Clockwork

precision on the barrack square is the first and most essential

preliminary to intelligent co-operation on the field of battle.

Much more might be said on this subject, but I must not wander too far

from my point. The few brief and incomplete remarks I have made will

suffice to prove to you that true collective discipline does not exist

to any appreciable extent amongst the civil population of the United

Kingdom and that they do not understand the value of the timely,

careful, and complete preparation for war.

Now perhaps some of you may be wondering why I have dealt with this side

of question at all; you may be asking yourselves why I have thus pointed

out to you the shortcomings of the civilians whose ranks so many of you

have only just left. My object was not to put you out of love with your

fellow-countrymen, I wished primarily to impress upon you the magnitude

of the responsibility which their attitude towards military services

throws upon your shoulders. I want you to appreciate to the full the

fact that it lies with you and your comrades in the Navy and Army to

supply that in which the Nation as a whole is deficient. The few must

make good the defects of the many, therefore the qualities of the few

must be of very high order indeed. You may think you are being set an

impossible task, perhaps you are, but you must nevertheless strain every

nerve to perform the impossible so that at least the best possible is

achieved. My second object was to lead up to what I may call the “point”

of my whole lecture, viz.: The light in which you, in your present

capacity as soldiers, should henceforth regard discipline. First of all,

cast aside for ever the old popular prejudice that discipline is

something to be feared and disliked. Look upon it instead as something

to be proud of, as something which raises you far above the level of all

men who do not belong to the Army, just as law and order in a civilized

community raise that community far above the level of a nation of

savages. In your civilian days most of you were too young to think

seriously of social problems, but everyone of you was surely able to

realise the benefits which law and order confer upon this country, and

when you hear the words “law and order” from me now, your first thoughts

are not of the punishment such as fines and imprisonment – which might

have been inflicted upon you had you broken the law. You think first of

the law as being that which enabled you to live in peace and follow your

calling unmolested whilst your homes and property were protected. Why

then, when you hear the word “discipline,” should you think of

confinement to barracks and forfeitures of pay which you may have to

suffer if you infringe military regulations? Punishment is undoubtedly

frequently necessary, for even the best of horse occasionally requires

the spur, but fear of punishment alone is a very poor foundation for

military discipline which, to be perfect, should be submitted to readily

and voluntarily by all. Try and learn the value of discipline in the

fullest and highest sense of the word, try and acquire sufficient

strength of will to perform conscientiously and well every single duty

however seemingly small and unimportant it may be.

Practise self-control in all things and at all times, for instance, even

when you are only standing at attention on the barrack square. You

learned to stand almost before you learned anything else, and yet how

often have you been “pulled up” during the last few weeks for not

standing absolutely still, and so proving that you were unable to

control yourselves even for a few minutes. To many it may appear

ridiculous in the extreme for an officer to reprimand or perhaps even to

punish a soldier for not standing still. “What on earth does it matter,”

they would say, “if a soldier moves his hand or his head in the ranks?

Why do you waste so much time over such absurdities? They can only be

for show purposes, and men will not fight better for them. Why should

you worry men by treating them in such a childish fashion. It is little

short of madness.” All that may be very well in its way, but there is

method in such madness all the same. Nobody wants to worry men, and the

British Army has proved often enough that it does not exist for show. It

is no pleasure to officers of N.C.O.’s to have to find fault and check

the smallest wrong-doings, but checked they must be, especially in young

soldiers, in self-control and a sense of discipline are to be developed

in them. Men must learn to concentrate their attention on small, simple

matters before they can be expected to do so in more difficult

circumstances.

No half-trained or half-disciplined troops will ever do what they did in

those piping times of peace, nor will they ever do what such men will do

cheerfully and readily in the hard and bloody school of war, and after

all, it is for war and war alone that soldiers exist.

This may be a very self-evident truth, but it is one well worth

remembering and pondering over at times. In the monotony of daily

routines some men are apt to find their work dull and irksome, and I

speak from experience, it certainly is not highly interesting or amusing

to do a couple of hours sentry-duty on a cold, wet night. Again, to some

few soldiers and to a large majority of civilians much of the work we do

appears unproductive because there is little or nothing to show when it

is finished and because it brings in no immediate return either in kind

or money. “But what influence can I have on the moral force of the

people? I am only one man amongst many millions in the Nation, and only

one amongst some hundreds of thousands in the British Army.” Quite so,

but you are nevertheless an integral part of both the Nation and the

Army, you are one complete stone in the great edifice, and it is your

duty to see to it that you are hard and sound. The work you do may seem

insignificant and useless, but remember that it is nevertheless a part

of the sum total of work that has to be done and, as soldiers, remember

all of you that every atom of your work is some sort of preparation for

the bloody game of war, that life and death struggle between Nations, so

little understood by those of you fellow countrymen whom you have left

behind in civil life. No matter how unimportant a duty may appear, do it

to the best of your power, back up your No. 1 in the running of his

sub-section, and your captain in the running of his company so that he

may have full confidence in you. Groom yourselves thoroughly, make your

equipment and rifles glitter and shine, do your picquet and sentry

duties as though the lives of others depended upon your vigilance, aim

your rifles accurately, much may depend on the flight of the bullet. It

was one single well-aimed bullet that killed Lord Nelson, and deprived

Great Britain of one of the finest public servants she has ever had. In

short, pay the utmost attention to every little detail. Learn as much as

you can from your superiors, they are only too willing to teach and help

you; and stand by each other as soldiers should. Be truthful and obey

readily and willingly but without servility which is unworthy of a

Britisher. Strive each and everyone of you to become a sound and useful

part of the whole. Remember that you wear the King’s uniform. Practise

“discipline” in the fullest and highest sense of the word, it will raise

you far above the level of ordinary men, and it will enable you to

maintain the high reputation of The Machine Gun Corps and of the Army.

Remember that there is but one object in the whole of the long and

complicated process of your training. It is to teach you to be ready to

kill, kill quickly, and to be ready to kill again.

Lecture on Discipline given by Captain T J Gardner, The King’s Own

Regiment. Circa 1917 when Gardner was attached to the Machine Gun Corps.

Accession Number: KO2946/04

© Images are copyright, Trustees of the King's Own Royal Regiment Museum.

You must seek permission prior to

publication of any of our images.

Only a proportion of our collections

are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display

in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of

our collections which are held in store.