Soldiers of the Regiment

Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Dykes

The

museum is very pleased to report the acquisition of a collection of

papers relating to Alfred McNair Dykes of the King's Own Royal Lancaster

Regiment. Alfred Dykes was commissioned into the regiment in 1894

and served with both the 1st and 2nd Battalions, including active service

in South Africa 1899-1902 where he was wounded at

Spion Kop.

Listing of the Letters & archive of Lieutenant

Colonel Alfred McNair Dykes, 1885-1914

Captain Alfred Dykes in 1901 photographed in Dundee,

South Africa.

Accession Number KO2654/052

Lieutenant Colonel A M Dykes

Accession Number: KO0460/05

Colonel Dykes took command of the 1st Battalion, King's Own Royal

Lancaster Regiment, in 1913 and it was he who led them to France on 23rd

August 1914 - he was killed at Le Cateau three days later as the German

army advanced into France.

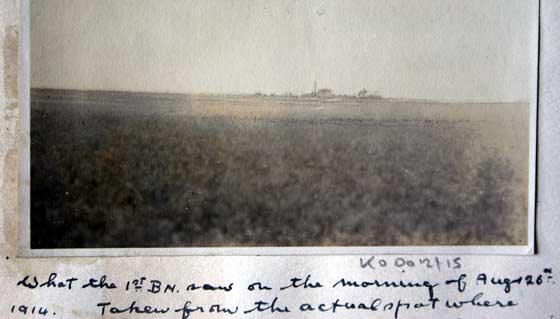

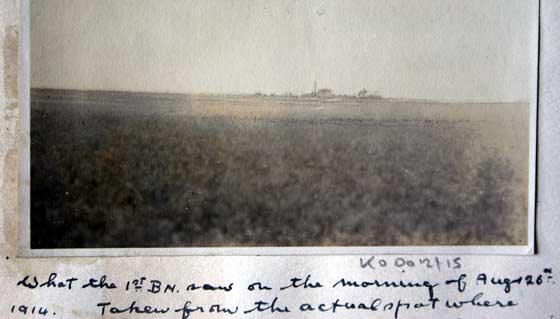

"What the 1st Battalion saw on the morning of 26th August 1914.

Wambaix Station in the background. Taken from the actual spot

where Lieutenant Colonel Dykes was killed."

Accession Number: KO0012/15

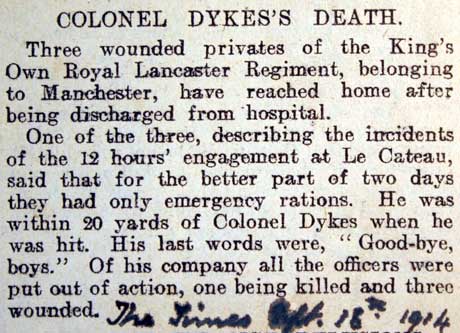

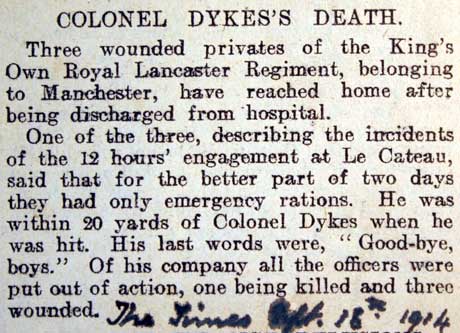

The Times Newspaper, September 1914

Accession Number: KO2654/099

The archive was purchased at auction in December 2006 and includes

family letters, photographs and other items of interest.

Photograph showing the 2nd

Battalion King's Own Royal Lancaster Regiment crossing the Zand Spruit at

low water between Dundee and De Jagers Drift. Alfred Dykes is

standing next to the horse on the river bank.

Accession Number KO2654/056

As the First

World War started, Alfred Dykes wrote to his mother on 5th August 1914:

“I was fully convinced

that unless we, as a nation, were to sacrifice our honour, we were bound

to go to war. First, in accordance with our most solemn obligations to

France and Belgium. Secondly, to preserve our existence as a Nation and

an Empire. Consequently without waiting for orders, I got to work at once

on the great work of mobilisation, last Monday morning. I am now

thankful; for though we are terribly busy, a great deal was done before

the order arrived yesterday at 5 O’clock. We are now more than a day

ahead of our programme and have saved a great deal of rush. ….we are

awaiting the arrival of reservists, who will be pouring in tomorrow and

subsequent days. My battalion will then be 31 officers and 1037 other

ranks. [Battalion Orders of 4 Aug 1914 listed peace time strength of

631].

One thing only I do ask

you and that is to accept the news and whatever comes of it, with the calm

strength and bravery which you have always shown in times of stress. We

are all happy and full of confidence and I think that rarely never did war

begin in a more thoroughly just cause.

You used to think me

cynical, I think, in our Billiard Room War Councils when I used to air my

views on the value of German Treaties, Vows and Protestations. There is

no need to ‘crow’! The truth of all I said stands self evident today. On

the heads of the German and Austrian Emperors, who have plotted and

planned all this, for years, while professing peace…..”

Accession Number

KO2654/036

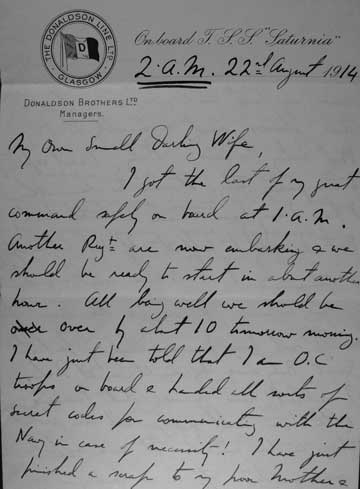

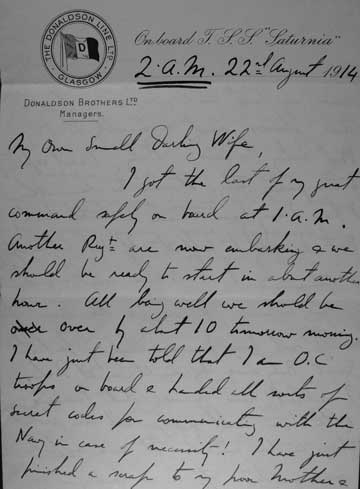

The last letter

from Dykes to his wife, written on board the SS Saturnia on board which

the 1st Battalion travelled to France on 23rd August 1914.

Accession Number KO2654/040

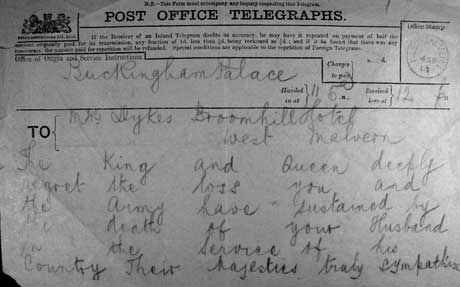

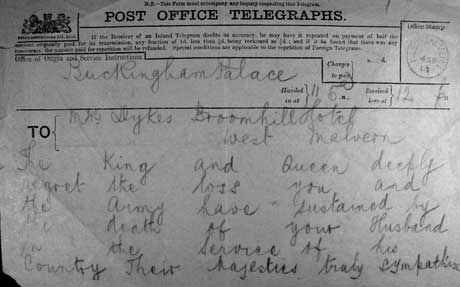

Telegram from Buckingham Palace, dated 4th September 1914 to Mrs Dykes,

Broomfield Hotel, Malvern. “The King and Queen deeply regret the loss you

and the Army have sustained by the death of your husband in the Service of

his Country. Their Majesties truly sympathise with you in your sorrow,

Private Secretary”

Accession Number KO2654/042

11th September 1914 - Lancaster Observer

The “Roll of Honour”

How Colonel Dykes was Killed. Officers’ Bravery and Heroism

A story told by a sergeant of the King’s Own gives some brief intimation

of how Colonel Dykes and two of his officers met their death. Here is

the story, told with laconic bluntness – a soldier’s description, in

fact, of an engagement which a war correspondent would have been able to

present in thrilling fashion: The King’s Own with the Lancashire

Fusiliers and the Middlesex Regiment were ordered to cover the retreat

of the allied forces from Mons. On Tuesday 25th August, they left the

position in which they had been entrenched to take new ground, and were

marching through the night, finding themselves at day break between

Cambrai and Le Cateau. Several French regiments and a Highland regiment

had passed their lines, when as the King’s Own were taking breakfast,

the German artillery boomed forth. Several shells fell in the vicinity

of the trenches without doing much harm, but the enemy’s artillery was

much superior in numbers to that of the allies, and they poured in a

raking shrapnel fire before the English guns began to speak. There was

no doubt either about the enemy’s range finding, under cover of the guns

the enemy came on in the proportion of six to one. Men were mowed down

like ninepins by the bursting shrapnel, and it seemed as though the

King’s Own had been singled out for the special fury of the onslaught.

Colonel Dykes fell at an early stage of the engagement while shouting

encouragement to his men. Fighting continued furiously from 4.30 until

9.30. Then there was a lull, and the enemy, seemingly reinforced, made

good their advance, and another five hours’ desperate conflict ensued.

The allies fought the advance inch by inch, fighting becoming so close

that the King’s Own got home with several dashing bayonet charges. One

of the most brilliant of these bayonet charges was led by Captain

Clutterbuck, who, with a handful of men, routed four times the number of

men under this command. He paid the price of his gallantry with his

life, but the casualties to his men were singularly light. The sergeant

said, “It was just like Clutterbuck.”

“Then,” continued the sergeant, “there was Lieutenant Steele-Perkins,

who died one of the grandest deaths a British officer could wish for. He

was lifted out of the trenches wounded four times, but, protesting,

crawled back again till he was mortally wounded. The first man knocked

over was one of the most popular of the Rugby footballers in the Dover

garrison. He was shot through the mouth. Lieutenant Woodgate

distinguished himself in bravery, and Major Parker was coolness

personified.

“A German aeroplane,” proceeded the sergeant “which came over our

position on the day preceding the battle was accounted for; assailed by

a shower of bullets from more than one regiment, its reconnoitring

career had a sudden stop. The enemy swooped down on us so quickly at the

finish that we were unable to remove all our dead and wounded. Stretcher

bearers were shot down, and I, who had been wounded with a shrapnel

bullet in the muscle of the left arm, was taking a message for the

doctor from the field hospital (a school) when a shell came and

demolished the roof. All the King’s Own dead are buried in France, a few

miles from the frontier. We saw many burning villages, and our artillery

helped along many old women and children who were fleeing before the

enemy.”

Colonel Dykes’ Distinguished Career

Colonel Dykes was born in 1874, and was the son of the late Mr William

Ashton Dykes, of The Orchard, Hamilton, NB, an of Mrs Dykes who is still

alive. He was educated at Glenalmond, and in 1894 received his

commission in the King’s Own, passing in through the militia. He

received the highest number of marks of any of his competitors. In his

early twenties, as a subaltern, he became adjutant of the regiment,

serving in that capacity in South Africa, rejoining his regiment after

having done duty for a short time as embarkation officer. He was

dangerously wounded at Spion Kop, in the vicinity of the Boer Trenches,

and an endeavour to locate their exact position. He was invalided home,

but in a few months he returned to the seat of war, where he was

employed on convoy duty. He distinguished himself in the defence of

Vryheid, successfully repulsing an attack by Louis Botha in greatly

superior numbers. He was twice mentioned in despatches, and was offered

the choice of DSO or a brevet majority. He chose the latter, being then

but 27 years of age. He received the Queen’s medal with four clasps, and

the King’s medal with two clasps. He was staff captain at the War Office

between 1904-08. He had also passed through the staff college, and for a

short time he was in command of a company of gentlemen cadets at

Sandhurst. On the death of Colonel Marker in August last year he was

appointed to the command of the 1st Battalion of the regiment. He was

then but 39 years of age, and was the youngest lieutenant colonel in the

line. To his fine soldierly qualities were added an extreme personal

charm, and inexhaustible fund of humour. He was beloved by both officers

and men in all the positions he occupied. On the 21st April this year he

was married in London to Rosamund Ann, daughter of the late Mr Frederic

Willis Farrer, and of Mrs Farrer, of 26 Palace Court.

6th November 1914 - Lancaster Observer

Soldiers’ Stories

Another story of Colonel Dykes’ Death.

Private James Ford, of the King’s Own Royal Lancasters, who is at

Northwich wounded in the foot, has re-told the story of the engagement

forty miles from Mons. He said:- “Our colonel was the first man to die.

It was a brave sight, and I shall never forget it. As he lay on the

ground he shouted, ‘Good bye, boys’ and then passed away. This was a

brave death, and that of a true Englishman. In all 640 of our men went

down, and the regiment was terribly cut up. As we retreated, doing no

less than thirty miles in a day, we came across women and children

fleeing from the scene of battle. The Uhlans are a bad lot, and are far

worse than the ordinary German soldiers. When I was struck on the foot I

fell against a tree and broke my watch. It was a knack of our men to

crowd all sorts of small articles into their clothing, thinking they

might stop a bullet or reduce its speed. I have known many cases of

lives being saved in this manner.