|

King's Own Royal Regiment Museum Lancaster |

|

|

HOME Museum & Collections Sales Donations Events Contact Us REGIMENTAL HISTORY 17th Century 18th Century 19th Century 20th Century First World War Second World War Actions & Movements Battle Honours FAMILY HISTORY Resources Further Reading PHOTO GALLERY ENQUIRIES FURTHER READING LINKS

|

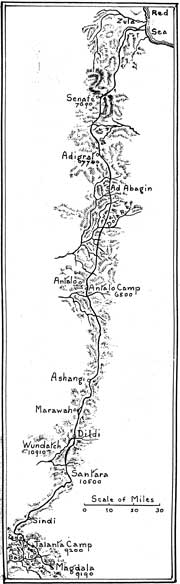

Regimental History - 19th Century - Abyssinian Campaign March to Magdala An account of the expedition and sponsored walk undertaken by Peter Donnelly, Curator, King’s Own Royal Regiment Museum, in January 2003. In 1868 the King’s Own was one of three British regiments which took part in an expedition to Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in order to secure the release of a number of Europeans who had been taken hostage by Emperor Theodore following a diplomatic dispute. The entire force marched 380 miles from the Red Sea to the fortress of Magdala, where they engaged and defeated the Abyssinian Forces and secured the release of all the hostages. The map (lower left) illustrates the route of the original expedition which was led by Sir Robert Napier. The King’s Own landed at Zula on the Red Sea and marched from there, through what is now Eritrea, to Magdala. Because the border area between Eritrea and Ethiopia is presently under the administration of the United Nations and closed to visitors my walk starting at Ashangi, was somewhat shorter. I flew into Addis Abba, the Ethiopian Capital, and joined up with the others who were taking part in the expedition, under the leadership of Major General (retd) Sir Evelyn Webb-Carter, Colonel of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. From Addis we flew to the Holy town of Axum in the North and then drove two days to get to the starting point of Lake Ashangi. In 1868, Colonel Cameron of the King’s Own walked the entire route to Magdala, and back, while Lieutenant Borrett, whose letters form a wonderful diary of the expedition, purchased a mule which he rode for some distance and walked only when the mule gave up on him. I decided to walk, like the Colonel. Day one took us from Ashangi, through Mussaha where the army had camped overnight, to Lat. Being fresh and keen we had covered two sections of the march on this first day. The route was flat at first, but then rose considerably up a narrow pathway alongside a mountain stream. The path was busy with local people going about their business, but interested in who all these white people were! We settled a Lat overnight, with our camp across the main track causing some surprise to the locals who suddenly came across a nomadic settlement. I felt that we had taken over their place - and expected them to accommodate us rather than we work around them. Rather sad really. From Lat we walked to Marawah Camp where we camped in the school grounds - raising much interest from the children. They were overpowering with their enthusiasm but it was interesting to meet some local people. We left Marawah on the morning of market day and for the first couple of hours travelled a route which we passed hundreds of people heading in the opposite direction as they headed to the market with their animals. We were about 8000 feet above sea level, the terrain was undulating touching on mountainous and the conditions were warm and sunny. I was starting to suffer a little from dehydration and on arrival at the overnight camp at Dildi had cramp in both legs. This was however relieved by a large intake of fluids. Day four took us from Dildi, over the 11000 feet high mountain top at Wundatch to Muja Camp. As we approached the summit it became much colder but fortunately the sun continued to shin. Looking back during the descent I could see that the mountain top was now enveloped in cloud and it would no doubt be much colder up there. At Muja the mules on which the others in the party were riding and on which the baggage was carried were changed for fresh ones. This involved much discussion and haggling between the local porters and muleteers and our guide Solomon but things were eventually sorted out and we were ready to move on the next morning. From Muja we went, via the River Takazze which eventually flows into the Nile, to Santara Camp about 10500 feet above sea level. The climb to the camp was very hard and we arrived well in advance of the baggage mules with the result that it was dusk when the tents were being pitched. After sunset and with low cloud it became extremely cold. It was here that Lieutenant Borrett noted that ice had formed on the inside of the 12-man tents which the army used. During the 1868 campaign the temperature ranged from 110°F (40°C) during the day and 12°F (-10°C) at night and as ice formed on the inside of our tents I realised that conditions for us must be very similar. The next day is Christmas Day in Ethiopia and was spent as a rest day. I don’t remember much because not feeling well, I spent most of it asleep and the most energetic thing I did all day was wash my socks in the river. The next day involved an easy march along a flat plateau but, probably because I hadn’t fully recovered from whatever had affected me the previous day, I started to lag behind the rest of the party. Because of his concern for me the General persuaded me to ride a mule which I did for only about 3 miles. After some warming tea I felt much better and continued on foot, as at 10000 feet, we went via Gahso, Abdikum and Sindi to Bethor Camp. The next day was another rest day and to be honest I also spent that day doing very little! At Bethor I could feel we were much closer in the same way Lieutenant Borrett must have done in 1868. He records that intelligence was being received as to what was happening at Magdala, which by now was less than 40 miles away. We left Bethor Camp and dropped down a couple of thousand feet to cross the River Jeddah then climbed again to the top of another plateau which was a similar height to the one which we had just left. It must have been about 6 miles as the crow flies but more than 14 miles by our zig-zag route and about 3000 feet down and another 3000 feet back up again! Lieutenant Borrett records that these were particularly difficult and steep descents, with river crossing and steep ascents - the worst of the whole route. I had by now dispensed with my day-sack, which contained spare water and my camera, which was carried by a mule allowing me to travel much lighter than before. I’m just glad I did not have a Snider rifle to carry as well. Once across the Talanta plain we dropped down even further than the previous day in order to cross the Bashilo River. Our route now deviated from the original of 1868 and instead of advancing up a difficult feature called the Gombage Spur, as the King’s Own had done, we followed the route which the baggage train had taken along a dried up river bed. That night our camp-site was a couple of thousand feet below those of previous nights and as a result this was the warmest night so far. Day thirteen took us to Arogie where the King’s Own had engaged the forces of Theodore and inflicted a heavy defeat which opened the way to Magdala. There was no evidence that a battle had taken place at this site of that the King’s Own had ever been, the only changes since 1868 appearing to be a modern brick built school and the sound of the petrol engine of a machine used to grind grain. Battle of Arogie When Theodore witnessed the arrival of the British baggage he foolishly assumed it was unguarded and unleashed his forces from the heights of Fala. On seeing this the King’s Own, although exhausted from their day’s march, rose to their feet and the battle commenced. Faced with troops armed with the Snider repeating rifle the Abyssinians did not stand much chance and were easily defeated. Theodore withdrew to Magdala, the other local chiefs surrendered Fala and Selassie without resistance leaving Magdala to be stormed by the 33rd Foot, later Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. From our campsite at Arogie we made the final advance, up to the heights of Fala, Selassie and Magdala, three peaks which dominate the surrounding countryside. Again little evidence survives of what took place all those years ago now survives with the only exceptions being two very large mortars which were too heavy to be moved for use elsewhere. The original burial place of Theodore here at Magdala is marked by a large standing stone and a surrounding wall but his body was long ago moved and re-buried elsewhere. Magdala is still very remote and to complete our expedition we had to walk another six or so miles to Tenta, the nearest village with a road. It was market day in the village and this time we were walking in the same direction as the locals, a very colourful end to the journey. Local People Along the way we met many local people most of whom had never before seen a white person while others had seen only one or two. We were of great interest to them and throughout the journey our campsites always attracted a group of spectators. The main occupation of the locals is subsistence agriculture with grain, cattle, sheep and goats being farmed all along our route. The locals sold us eggs, bread, chickens, sheep, goats and firewood. Many of the children were learning English at school - and in one village we held an impromptu English lesson with me pointing at the pictures in the book and they would all shout the answer. When not at school children could be found in fields taking care of the animals. The Table In Borrett’s letters home he frequently complained about not having a table to write on. It is with a great sense of irony that I wish to record the sterling efforts of our porters who managed to carry three metal folding tables the whole way. Sadly the mountain paths proved to be too much for one of the tables which was left a Magdala. In some ways I would have liked to have not had the luxury of tables, but I’m sure Borrett would have smiled! Food and Drink With regard to drinks there were both tea and coffee and I found the tea to be particularly pleasant and refreshing. The typical Ethiopian way of serving it is with lots of sugar and, occasionally, a drop of local spirit alcohol. Throughout the journey I drank lots of water so when, after crossing the river Takazee, we found somewhere to buy bottles of fizzy drink it was most enjoyable to have something a little different. The food at lunch time was simple and included boiled eggs, potatoes, corned beef and bread. I tended to ignore the sardines which were occasionally offered and opted for a tin of meat paste and ‘biscuits brown’ - which I had taken with me for just such an eventuality. Evening meals included soup, pasta (a left over from the Italian occupation in the 1930s) tinned and fresh meat, goat, sheep and chicken. Much of the food was prepared with hot spices, and I have a feeling that this may have been a factor in the digestive troubles which I experienced during the trip. My luxuries of juice powder, hot chocolate, boiled sweets and a couple of bars of chocolate were certainly welcome. I wish I had taken more - but I’m now sounding like Lieutenant Borrett who wished he had taken some in the first place! The Guides Solomon, our guide, had organised the trip and was responsible for the day to day supervision of the porters, cooks and muleteers. He had travelled the route previously with a group from the British Council and was a font of knowledge particularly regarding the local wildlife. China, who had served in the Ethiopian army but now worked on these expeditions, was our cook. He was assisted by two men, Masala and Halifum, who lived at our starting point at Ashengi and who, after walking to Magdala, enjoyed the luxury of travelling home by bus. In addition to the permanent staff we had many porters, muleteers and camp followers who added to the colour of the expedition! The Famine Question Shortly after I booked to go to Ethiopia there was considerable publicity about the famine in there and, to be honest that is probably what most people associate with the country. Contact with both Solomon, and the British Embassy, revealed a few facts of interest. The famine was limited to the south of the country and had we decided not to go on our expedition we would have done more harm than good. Tourism is becoming increasingly important to the economy of the country, with each tourist directly affecting the employment of over 15 people. These include the workers at the airport, hotels, restaurants as well as, in our case, the porters and muleteers who travelled with us. The money which we took into the local economy was highly valued; it will only be through further tourism that the economy will be able to improve and diversify from the fragile subsistence agriculture which now dominates. Sponsorship At the end of February, I am pleased to report that over £1,600 has been raised for the Museum’s Conservation and Acquisition Fund. There has been an excellent response to the appeal, and I must admit the thought of the sponsorship did keep me going on some of the particularly hard days! We recommend the book: ‘My Dear Annie’ ‘My Dear Annie’, published by the museum, features the letters which Lieutenant Herbert Charles Borrett wrote to his wife Annie during the Abyssinian Campaign of 1868. His first hand account provides a fascinating commentary on the expedition, from the time Borrett set sail from India, to his return to the United Kingdom. His first hand contemporary account of the battle of Arogie and the storming of Magdala are wonderfully detailed. Priced at £7.50 including postage. Please see our sales page for ordering information. For more information about the Abyssinian Campaign we also recommend The King's Own The Story of a Royal Regiment Volume 2 1814-1914 by Colonel Lionel I Cowper - the best history of the King's Own. On a CD-rom, viewable through a computer. Price including UK postage £12.75 The guide for the tour, Solomon Berhe, has a website: http://solomonberhetours.com |