HOME

Museum &

Collections

Sales

Donations

Events

Contact Us

REGIMENTAL HISTORY

17th Century

18th Century

19th Century

20th Century

First World War

Second World War

Actions & Movements

Battle Honours

FAMILY HISTORY

Resources

Further Reading

PHOTO GALLERY

ENQUIRIES

FURTHER READING

LINKS

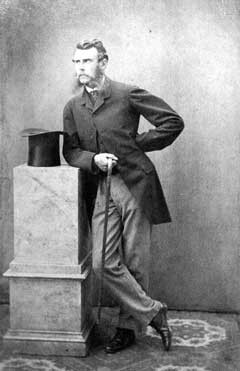

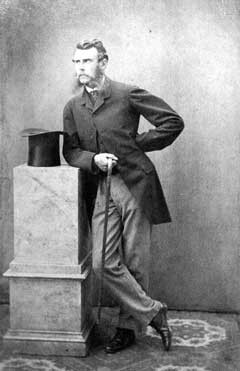

Captain James Paton, 4th King's Own, at Chatham,

1862

Accession Number: KO2590/394

|

|

Soldiers of the Regiment

Major James Paton

Recollection of the Crimean Campaign

Told by Major James Paton of Crailing on an evening in October 1921

This little account of a war fought in a bygone day will make us

realise what a different age we now live in.

In the Crimea the poor soldiers spent the winter in such conditions that

a large proportion of them died; not from wounds but from sickness

brought on from actual want of the necessaries of life; from want of

proper attention when ill and from lack of hospitals, nurses, medicine

and surgeons.

Under what different circumstances our men fought in the Great War you

will now realise.

If the war of 1914 had been fought under the same conditions as the war

of 1854 I wonder how many of the men would have lived to return?

It is wonderful to think that this little account was told me by a man

of ninety years of age. Who lived through the Crimean war & who came

through it so fit and well that when it was over instead of coming home

he went on to India to take part in quelling the Mutiny.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

I embarked with my regiment the 4th King’s Own on the 4th of March 1854.

It is one of the oldest Regiments in the Service as it was raised in the

Reign of Charles the Second. The Royal Scots however is older.

I was quartered in Edinburgh when the war broke out and when the orders

for active service came I marched in with my Company from Greenlaw

(where I had been doing duty) to Granton where we embarked in a sailing

vessel called “The Golden Fleece”.

Edinburgh was a very different place in those days and Princes Street

was composed entirely of private houses. There was little or no traffic

there, in fact it was just as quiet as ?not clear

At the beginning of the great war all the men went off singing

“Tipperary” but in 1854 they all sang “Annie Laurie”. There was the

greatest excitement you can imagine and large crowds collected to see us

embarking fact there was more excitement shown than in August 1914.

In the great war we fought against the Turks but in the Crimea we fought

with them.

Malta was our first stop and we were there for three weeks. We then

proceeded to Gallipoli in the “Emu” and remained there for three months.

The weather was very hot and we bathed every day and had battle in the

sea – one Reg. against another.

Unfortunately that dreadful scurge – cholera – now broke out & we lost

an officer and many men. We were then moved on to Varna in Bulgaria

(Don’t some of these names bring back the great war to you?) “where the

expeditionary force was collecting in the Bay. We were there for a month

and cholera was very bad all the time. When the men died their bodies

were sunk in the sea with shot but they used to bob up again.

We went on to the Crimea in a sailing ship called the “Diva” which is

the Roman word for Die. A steamer used to tow two sailing vessels. There

were very few steamers in those days. The sea was covered with ships

taking a large army (Large in those days) – about 25,000 men.

We landed on the open beach on Sept the 14th and the weather was vary

warm. I had dysentery and could not land with the Reg. The day after

they landed I went ashore in a boat by myself without leave and joined

the Reg though I was very weak. The result was that the next day I was

sent on board a ship taking the sick to Constantinople.

There were two hundred men on board in all stages of cholera. They

simply laid down on the bare boards on the deck and died there under the

most shocking conditions possible with no nurses, no medicine and no

sanitary conditions at all. I think there was one Surgeon with an

assistant. Thus we went on to Constantinople throwing the dead overboard

all the way.

I soon got well again (I think this was quite a miracle – Editor) and

applied to the C.O. to return to my Regiment. He however refused as

officers were wanted to look after the wounded coming from the Alma.

Then I saw a steamer in the Bospherous Taking the Royal Dragoons to the

Crimea. Now was my chance. I asked the Officer commanding the Royal

Dragoons to take me with them and he consented to do so (Without leave).

So I went and joined my own Reg. on Oct. the 3rd.

The Siege of Sebastopol was just beginning. I walked six miles from

Balaclava to Sebastopol and found the Reg. camped out in tents. We had

plenty of salt junk, ship’s biscuit, and green coffee. This was the

beginning of the most fearful winter imaginable. We had nothing but the

clothes we stood up in.

We fought in anything we could find to keep out the cold.

I wore a sailor’s pea jacket. Winter started on Nov. the 14th. There was

an awful storm which blew down all the tents and numbers of ships were

wrecked. We were the nearest Reg. to Sebastopol near a valley called

“The Shadow of Death”. We used to go into the trenches in turn for

twenty four hours at a time and sometimes I used to go to sleep standing

up.

The men were dying of disease every day – Cholera, Typhus and frost

bite. There were no Nurses yet, no hospitals or medicine and very few

Drs. There was just a tent pitched on the hill side on the bare ground

where the sick men were laid and of course they usually died. The Army

landed with no transport at all, if you can imagine such a thing. No one

can really imagine the sufferings of the troops during that dreadful

winter. As the men only had salt junk they soon got scurvy. At one time

they were able to dig up some sort of roots they could eat gut when the

frost and snow came this became impossible. We went out into the

trenches and were so wretched that we did not care a rap whether we came

back or not. The Reg. was reduced from 600 men to 70.

On Xmas Day the Commissariat had collected enough cattle to give us some

fresh meat but as a matter of fact some French Souaves made the guard

drunk and stole the dinner so we just had salt junk and biscuit.

There was not very much actual fighting. The Reg. was dreadfully reduced

in numbers. The Russians made occasional sorties. The cold was awful and

some of us just managed to live. The poor animals suffered dreadfully

from hunger as little food could be procured for them. It was sad to see

the gun horses trying to eat each other’s tails in their agony of

hunger.

Then at last Spring came and things began to improve a little and

sometimes there was a little fresh food but generally the same and the

men with bad teeth died as they could bite the biscuit. One night in the

trenches an Officer had been posting Sentries and said he had not enough

men to communicate with the French Sentries who were next us. I was sent

with Corp. Hutchins to investigate and I found that there were actually

too many men so we proceeded back again. Just as we got to the Trench

and were going over the parapet a shell came and killed the Corp. and

the six men with us. Corp. Hutchins’ brains were all over my red tunic

and pieces of bone were blown into my face and body. I laid there

insensible for some time and then a brother Officer name “Cuddy Eccles”

came and carried me in. The C.O. applied for a VC for him but did not

get it. All that winter as I said before we fought in any clothes we

could lay hands on but after that sheep skin coats were served out to

us.

With the summer came good weather and more fighting and our Colonel –

Cobbe – was killed. After that we took the Redan, and Sebastopol fell on

Sept. the 8th 1855.

A day or two after this I went into a dugout in the town where the

Russians had been all winter. A Middy came in with white trousers on. He

went out again with dark brown legs nicely shaded up to white – Fleas –

thousands of them! And there was worse than fleas.

I was the only man in the Reg. under the rank of Field Officer who

received the Legion of Honour from the French. (His son who served the

great war in the Royal Navy as a Captain got the same decoration from

the French). After the place fell I took my Company down to the town of

Sebastopol to get stones to build huts. One day when we were hard at

work a hidden magazine exploded and killed 18 men. We built houses and

roofed them in.

At this time six of us had a mess and were fairly comfortable. We had

better food with a barrel of whiskey and one of sherry. Needless to

relate we had a good many visitors! These had been sent out to us by the

Sec. of State for war to one of my Brother Officers called Dowbiggin who

was his – Lord Panmuir’s nephew. Lord Panmuir wired out to the Colonel

“Remember Daub” and the Colonel did not understand and thought it must

refer to some out post where the enemy might attack and did not realise

he meant his nephew Daubiggin whom he wanted mentioned in dispatches.

This caused many jokes I was looking at an old “Punch” of the period

lately and saw something about “Daub”

My folk sent me out a barrel of raspberry jam which was much

appreciated. Tin boxes were unknown in those days.

After the first attack of dysentery I did not miss a single trench duty

except when I was wounded. Florence Nightingale came out to Scutari

then. We could have done with her a little sooner!

During the first winter I bought a pair of socks from an officer’s kit

who had been killed and paid 30/- for them! I heard of a man who had a

sheet of notepaper but as he would only change it for some tobacco the

deal did not come off!

During the second winter I was working on a road when a brother officer

came to me and said my ears were quite white. I took off my glove and

found they were frozen hard. I kept rubbing my ears with snow and fell

out and returned to Camp where I found my hand was frozen too. I

remember the great pain when they were doming round.

We left the Crimea in July 1856. When we returned to this country Queen

Victoria received us on horseback in Edinburgh in a blue habit and

wearing too a red coat.

: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :

: : : : : : :

God Save the King

Scatter his Enemies

and make them fall

When the war was over he was sent to India instead of ? – was at

an outpost after the Mutiny.

Only a proportion of our collections

are on display at anyone time. Certain items are on loan for display

in other institutions. An appointment is required to consult any of

our collections which are held in store. |